The continued progress in the economy has made Americans more confident about retirement. Recent upbeat data from the government may explain why the good mood prevails.

How Much Money do you Need to Retire?

As we conclude National Retirement Planning Week, it’s time to ask the perennial question: How much do you need to retire? The answer depends on a variety of personal factors, starting with how much you need to float your lifestyle today. Because so many people hate the idea of figuring out what they are spending now, they often use an old financial planning calculation to determine their retirement income need: reduce current salary by 20 percent. The rationale behind this strategy is that in retirement, people will no longer be on the hook for payroll taxes, retirement plan contributions or commuting costs.

Of course if you are living on far less than 80 percent of your current pay or some of your big expenses will disappear during retirement (mortgage, school loans), you may want to use a lower monthly need. Then again, according to a report by HealthView Services, the average couple should expect to spend $266,600 throughout retirement on health care. So maybe that 20 percent reduction is not such a bad substitute for your future monthly nut.

Once you have your retirement need in hand, you need to determine how much income you will receive from Social Security and pensions. Any shortfall between your monthly need and your stream of income has to come from your investments.

I continue to emphasize the importance of using a reasonable “withdrawal rate,” which is the percentage that retirees can safely withdraw from their assets annually without depleting their nest eggs. A conservative withdrawal rate is 3 to 3.5 percent on an annual basis. That means every $1 million you save can generate about $30,000 to $35,000 of annual retirement income.

The biggest problem in answering the question of how much do you need to retire, is that it requires a lot of moving parts to operate smoothly over a long period of time. As economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman says: “In an idealized world, 25-year-old workers would base their decisions about how much to save on a realistic assessment of what they will need to live comfortably when they’re in their 70s…In the real world, however, many and arguably most working Americans are saving much too little for their retirement. They’re also investing these savings badly.”

How badly are Americans at investing? A recent Bankrate.com study found that just 48 percent of Americans own stocks or stock mutual funds. Of those who don’t participate in the stock market, 53 percent say they simply don’t have the money to invest. Considering that median per capita income, adjusted for inflation, has basically been flat since 2000 and many Americans are still climbing out of a massive hole from the Great Recession, that result is not surprising.

But a whopping 39 percent cite reasons for avoiding stocks that are worrisome: 21 percent don’t know about stocks; 9 percent don’t trust brokers or advisors; 7 percent think stocks are too risky; and 2 percent are afraid of high fees. All of those rationalizations can be resolved without much work, especially in an age of abundant, free information and resources.

In honor of financial literacy month and retirement planning week, here are a few answers to questions that may be keeping people sidelined from the market:

What is a stock/Isn’t owning a stock risky? When you own a share of stock, you are a part owner in a publicly traded company. Stocks as an asset class are risky, which is why when most people invest, they use mutual funds and spread out their risk among different assets, like stocks, bonds, real estate and cash.

What if I don’t trust brokers or advisors and/or want to avoid high fees? To invest without an intermediary in an affordable way, just use no commission index funds. Some of the most inexpensive index funds are offered through Vanguard, Fidelity, T. Rowe Price, TD Ameritrade and Charles Schwab.

Bonds away: How to protect against rising interest rates

When investors look back at the spring of 2013, they may say it was the moment when the bond market finally shifted and a new trend of higher interest rates emerged. It appears that the long-awaited reversal of the bond market has begun. In early May, the yield of the 10-year treasury hovered at just above 1.6 percent. While that wasn’t the all-time low (1.379 percent in July 2012), it was pretty close. We have all known that bond yields would have to rise, eventually. We’ve known that at some point the fear of the financial crisis would recede, the economic recovery would become self-sustaining and the Fed would stop purchasing bonds. Whenever that occurred, the 30-year bull market in bonds would come to an end, pushing down prices and increasing yields

Many bond market moves look benign in the rear view mirror, but they can feel pretty dramatic in real time. The rise in 10-year yields from 1.62 percent in the beginning of May to a 16-month high of 2.35 percent in mid-June might not seem like a big deal – just 0.73, right? But it’s important to realize that it’s a 45 percent move in just 6 weeks!

What does that kind of move mean to your portfolio? It means that many of your bond positions have lost value, because as interest rates rise, the price of bonds drops. The magnitude of your hit is partially tied to the duration of the holding. Duration risk measures the sensitivity of a bond’s price to a one percent change in interest rates.

The higher a bond’s (or a bond fund’s) duration, the greater its sensitivity to interest rate changes. This means that fluctuations in price, whether positive or negative, will be more pronounced. Short-term bonds generally have shorter durations and are less sensitive to movements in interest rates than longer-term bonds. The reason is that bonds with longer maturities are locked in at a lower rate for a longer period of time.

For those of you who own individual bonds, the price fluctuations that occur before your bonds reach maturity may be unnerving, but if you hold them to maturity, you can expect to receive the face value of the bond.

If you own a bond fund, it may be scary to see the net asset value (NAV) of the fund drop when rates increase. To soothe you a bit, remember that when NAV falls, the bonds within the fund should continue to make the stated interest payments. As the bonds within the fund mature or are sold, they can be replaced with higher-yielding bonds, which could create more income for you in the future. Additionally, if you are reinvesting interest and dividends back into the fund, you may benefit from purchasing shares at lower prices.

To help protect your portfolio against the eventual rise in interest rates, you may be tempted to sell all of your bonds. But of course that would be market timing and you are not going to fall for that, are you? Here are alternatives to a wholesale dismissal of the fixed income asset class:

Lower your duration: This can be as easy as moving from a longer-term bond into a shorter one. Of course, when you go shorter, you will give up yield. It may be worth it for you to make a little less current income in exchange for diminished volatility in your portfolio.

Use corporate bonds: Corporate bonds are less sensitive to interest-rate risk than government bonds. This does not mean that corporate bonds will avoid losses in a rising interest rate environment, but the declines are usually less than those for Treasuries.

Explore floating rate notes: Floating rate loan funds invest in non-investment-grade bank loans whose coupons "float" based on the prevailing interest rate market, which allows them to reduce duration risk.

Keep extra cash on hand: Cash, the ultimate fixed asset, can provide you with a unique opportunity in a rising interest rate market: the ability to purchase higher yielding securities on your own timetable.

So even if this truly is the turnaround in the bond market that we’ve all been waiting for, there’s no reason to be afraid. Just pay closer attention to your bond holdings, and know how to protect yourself from rising rates!

Distributed by Tribune Media Services

Global market roller coaster: Stay on or get off?

During his May 22nd testimony on Capitol Hill, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke dropped a bombshell when he said that the Fed could pull back on its bond buying “in the next few [FOMC] meetings,” depending on prevailing economic data. Many investors interpreted the comment as a hint that the Fed’s stimulus was coming to an end. Remember that the Fed keeping interest rates low has spurred many investors into stocks, because they seemed preferable to cash, bonds or commodities. If rates start to rise, that decision may change. Guess what? Things are changing!

In the US, stocks are only down about 2 percent from the intraday high on May 22nd (now dubbed "B-Day" for Bernanke), but other markets are down more dramatically: bonds plunged about 7 percent; emerging market stocks have tumbled 10 percent; emerging market currencies are off sharply; and Japanese stocks have sunk 15 percent from recent highs.

With markets on a seemingly-unending daily roller coaster ride, here’s what you should do: NOTHING. This prescriptive measure is geared towards investors who have been sticking to their game plans and rebalancing ever quarter or so. If you are in that category, please sit still and don’t do anything.

But if you have been flying by the seat of your pants, use this market volatility as an opportunity to review where you stand, create a target allocation and force yourself to rebalance according to your goals.

Here are 6 more tips for every investor:

- Dont let your emotions rule your financial choices. There are two emotions that tend to overly influence our financial lives: fear and greed. At market tops, greed kicks in and we tend to assume too much risk. Conversely, when the bottom falls out, fear takes over and makes us want to sell everything and hide under the bed.

- Maintain a diversified portfolio. One of the best ways to prevent the emotional swings that every investor faces is to create and adhere to a diversified portfolio that spreads out your risk across different asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, cash and commodities. (Owning 5 different stock funds does not qualify as a diversified portfolio!)

- Avoid timing the market. Repeat after me: “Nobody can time the market. Nobody can time the market.” One of the big challenges of market timing is that requires you to make not one, but two lucky decisions: when to sell and when to buy back in.

- Stop paying more fees than necessary. Why do investors consistently put themselves at a disadvantage by purchasing investments that carry hefty fees? Those who stick to no-commission index mutual funds start each year with a 1-2 percent advantage over those who invest in actively managed funds that carry a sales charge.

- Limit big risks. If you are going to make a risky investment, such as purchasing a large position in a single stock or making an investment in a tiny company, only allocate the amount of money you are willing to lose, that is, an amount that will not really affect your financial life over the long term. Yes, there are people who invest in the next Google, but just in case things don't work out, limit your exposure to a reasonable percentage (single digits!) of your net worth.

- Ask for help. There are plenty of people who can manage their own financial lives, but there are also many cases where hiring a pro makes sense. Make sure that you know what services you are paying for and how your advisor is compensated. It’s best to hire a fee-only or fee-based advisor who adheres to the fiduciary standard, meaning he is required to act in your best interest. To find a fee-only advisor near you, go to NAPFA.org.

7 Investment sins

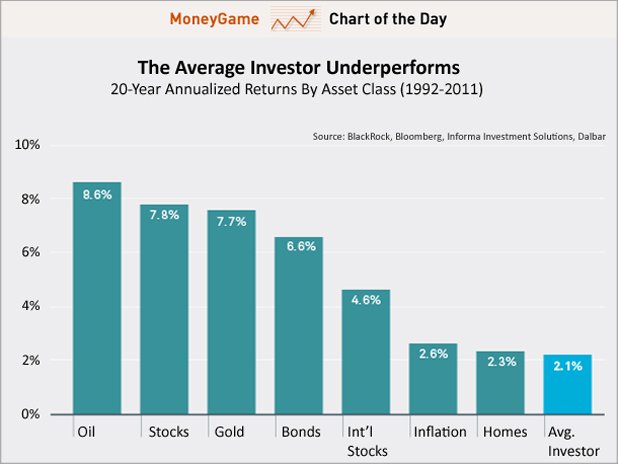

Hate to burst your bubble, but you are probably not a great investor. Need proof? Check out this chart from Blackrock that shows just how poorly average investors have been doing over the past two decades:

From 1992 – 2011, the average investor has only seen a 2.1 annualized return, compared to 7.8 percent for stocks and 6.6 percent for bonds. The explanation is obvious: investors feel good as asset levels rise, prompting them to buy; then after the asset plunges, some of those same investors panic and cash out.

The problem becomes even more pronounced during times of extreme market volatility and can leave a lasting impression. According to Bankrate.com’s Financial Security Index, a whopping 76 percent of respondents are simply avoiding stocks. Evidently, the combination of the worst recession since the Great Depression, plus the 55 percent stock market wipeout from October 2007 to March 2009 has made investors gun shy.

Economists call this “recency bias,” which means that we use our recent experience as a guide for what will happen in the future. So when stocks are soaring, we think markets will keep rising, but when the market plunges, we become convinced that it will never go up again.

Recency bias is just one of the 7 investment sins that continue to trip up investors—here are six more:

Allowing your emotions to rule your financial choices. There are two emotions that tend to overly influence our financial lives: fear and greed. At market tops, greed kicks in and we tend to assume too much risk. Conversely, when the bottom falls out, fear takes over and makes us want to sell everything and hide under the bed.

Not maintaining a diversified portfolio. One of the best ways to prevent the emotional swings that every investor faces is to create and adhere to a diversified portfolio that spreads out your risk across different asset classes, such as stocks, bonds, cash and commodities. (Owning 5 different stock funds does not qualify as a diversified portfolio!)

Timing the market. Repeat after me: “Nobody can time the market. Nobody can time the market.” One of the big challenges of market timing is that requires you to make not one, but two lucky decisions: when to sell and when to buy back in.

Paying more fees than necessary. Why do investors consistently put themselves at a disadvantage by purchasing investments that carry hefty fees? Those who stick to no-commission index mutual funds start each year with a 1-2 percent advantage over those who invest in actively managed funds that carry a sales charge.

Assuming too big a risk. If you are going to make a risky investment, such as purchasing a large position in a single stock or making an investment in a tiny company, only allocate the amount of money you are willing to lose, that is, an amount that will not really affect your financial life over the long term. Yes, there are people who invest in the next Google, but just in case things don't work out, limit your exposure to a reasonable percentage (single digits!) of your net worth.

Not asking for help. There are plenty of people who can manage their own financial lives, but there are also many cases where hiring a pro makes sense. Make sure that you know what services you are paying for and how your advisor is compensated. It’s best to hire a fee-only or fee-based advisor who adheres to the fiduciary standard, meaning he is required to act in your best interest. To find a fee-only advisor near you, go to NAPFA.org.

![Jill on Money [ Archive]](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/59efbd48d7bdce7ee2a7d0c4/1510342916024-TI455WZNZ88VUH2XYCA6/JOM+Blue+and+White.png?format=1500w)